Turkish Coffee: History, Coffeehouses & More

Discover everything about Turkish coffee, from its rich history and significance in Ottoman times to the vibrant coffeehouses that serve it. Explore the culture and traditions surrounding this beloved beverage.

9/25/202520 min read

General Discovery of Coffee

Introduction of Coffee to the Ottoman Empire

Spread of Turkish Coffee in History – Its Role in Politics

Prohibition of Turkish Coffee

Coffeehouse Culture

How It Differs from Other Coffees: Beans, Roasting, etc.

How It’s Made

Tools and Equipment

Varieties of Turkish Coffee Available in Turkey

Fortune-Telling Tradition

Different Uses of Turkish Coffee

Have you ever wondered how one of the world’s most global beverages, coffee, spread across different cultures?

According to Grand View Research, the global coffee market was valued at approximately 269.27 billion USD in 2024.

Although the way coffee is consumed changes according to culture, it has maintained its value throughout history and continues to do so today. Currently, Turkish Coffee holds a significant cultural value; in 2013, it was inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List, securing its place as a global cultural treasure. Based on my research from academic and official sources and the knowledge I have gained, today I will be introducing you to Turkish coffee.

But first, we need to start with the discovery of coffee.

The Introduction of Coffee into Human History:

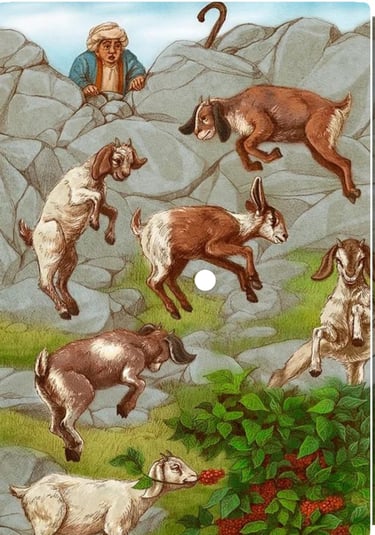

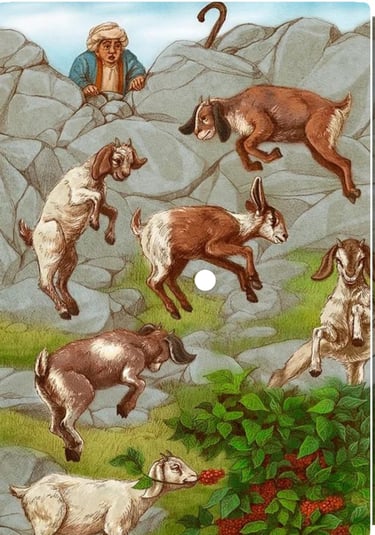

The oldest known story comes from the Kaffa region of Ethiopia. A shepherd named Khaldi noticed that one of his usually lazy goats became unusually energetic after eating the fruits from a tree. He then boiled and drank the fruit himself. This is how coffee was discovered.

According to another belief, Prophet Solomon visited a town during his travels and saw that the people were suffering from an unknown disease. Following the command of Gabriel, he gave them a drink made from coffee beans brought from Yemen, and the people were cured of the illness.

Another account tells of a Sufi from Mocha named al-Shadhili, who managed to survive in the desert for a time by consuming nothing but coffee. Upon discovering that it cured diseases such as scabies, some of al-Shadhili’s students learned about the benefits of coffee, returned to Mocha, and began to spread its use. There are various stories like these, and the claims differ depending on the source.

Whichever story is true, coffee found its way into our lives one way or another. Before it was consumed as a beverage, it was used as food.

As far as we know, in ancient times people made bread with coffee and consumed it regularly. In Ethiopia, this energizing fruit grew naturally and was turned into dried bread by travelers, who carried it with them as food. It was also used as a kind of medicine.

Etymologically, it is generally said that the name comes from the “Kaffa” region.

It is also said to have arrived in Yemen from Mecca or Medina.

Turkish coffee would go on to occupy such a significant cultural place that, according to sources, Turkish coffee became a fashion trend in Parisian society. It is also recorded that during the Ottoman siege of Vienna, the Ottomans left behind sacks full of coffee beans. Someone who frequently visited the Ottoman side during the siege asked what these beans were used for. After learning their function, he introduced coffee beans to Vienna.

However, because the major trade routes at the time belonged to the Ottoman Empire, its spread was not immediate or easy.

The Spread of Coffee Around the World:

From Ethiopia to Yemen, and then to other regions, its spread was inevitable. Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Sufi dervishes in Yemen used coffee to stay awake during night prayers, which helped popularize the beverage in its brewed form. It is said that coffee arrived in Yemen from Mecca or Medina. From there, it eventually made its way to Anatolia.

It is known that coffee entered the Ottoman Empire, specifically Istanbul, in the 16th century. The story differs depending on the source. According to one account, it was first brought to Istanbul by Özdemir Pasha, the governor of Yemen, who presented it to Sultan Suleiman. Thus, coffee was first consumed in the palace, then by the wealthy classes, and eventually it spread to the lower classes as well. Another article I read states that it was brought to Istanbul by Selim I in 1519 following his Egyptian campaign.

The details of how it was discovered, who spread it, and who first tasted it in the Ottoman Empire vary from source to source. But one thing is certain: coffee was loved.

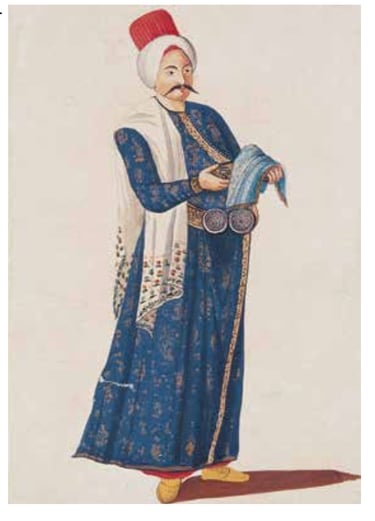

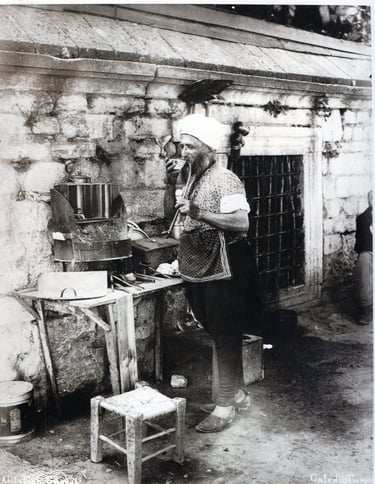

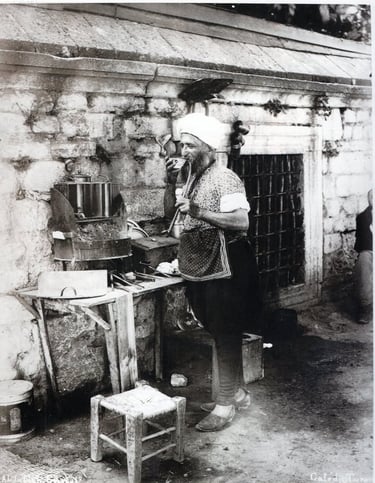

It is claimed that there was an official position in the palace called kahvecibaşı (chief coffee maker). The importance given to coffee grew so much that the water used to prepare the coffee for the emperor was brought from the Gümüşsuyu Fountain on Eyüp Hill in Istanbul.

At the beginning of the 17th century, about a century after coffee arrived in the Ottoman Empire, it was first taken to Italy and then to France by Ottoman merchants.

Through Mediterranean trade routes and ports such as Venice and Marseille, coffee entered Europe; coffeehouses opened in cities like Paris, Vienna, and London, and coffee became a part of European social life.

However, as mentioned earlier, most of the coffee production and trade routes at that time were under Ottoman control. Europeans sought ways to seize the plant and seedlings and transport them to their own colonies to gain direct access to the sources. The Dutch took seeds and seedlings to the Far East (especially Java) and established plantations; the French, British, and Dutch also brought coffee to the Caribbean and Latin America.

As a result, during the 18th and 19th centuries, coffee evolved from being a local beverage into a global agricultural commodity. Massive plantations were established in regions with suitable climates, and Brazil quickly became the world’s largest coffee producer. Thus, what was once a ritual drink spread throughout the world as a global phenomenon of trade and culture.

Kahvecibaşı descriptions:

Now, let’s travel back to Istanbul a few centuries ago.

Although the stories about who first brought coffee to Istanbul and who first drank it vary, one way or another, coffee arrived in the city—and it was quickly loved. In the Ottoman Empire, coffee began to be consumed as a pleasurable substance.

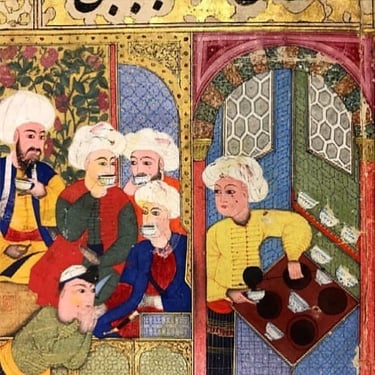

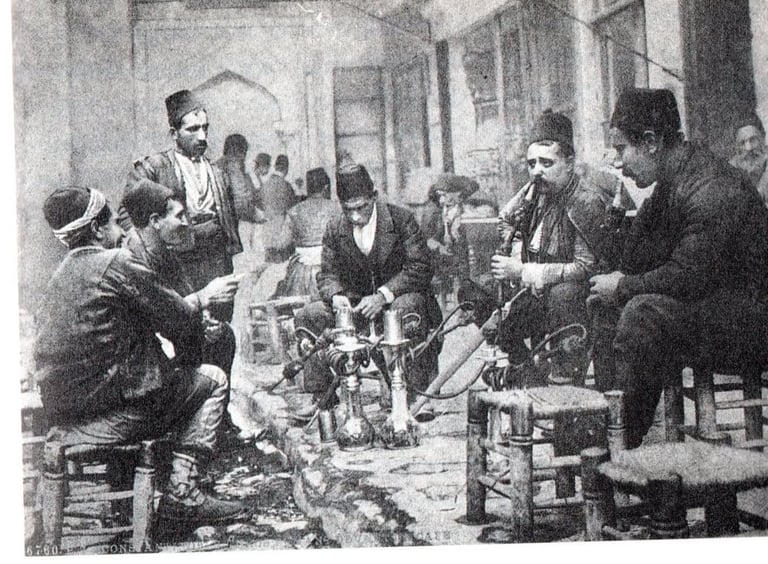

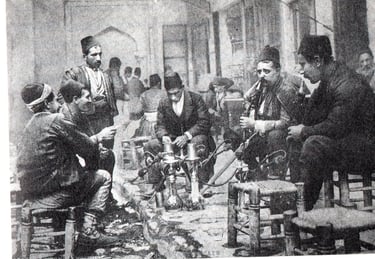

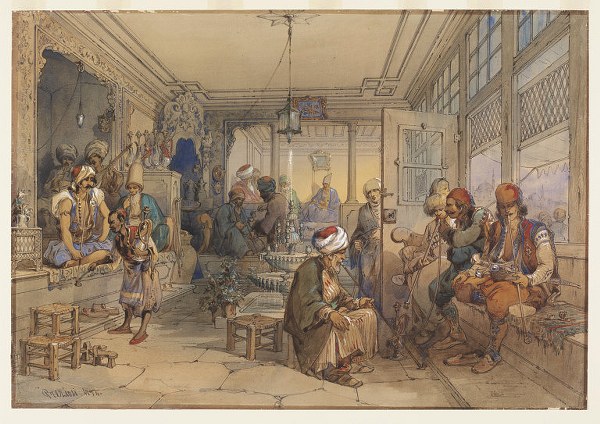

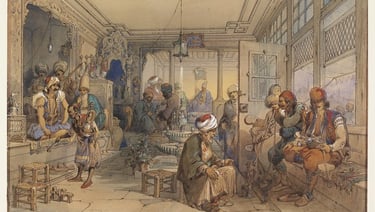

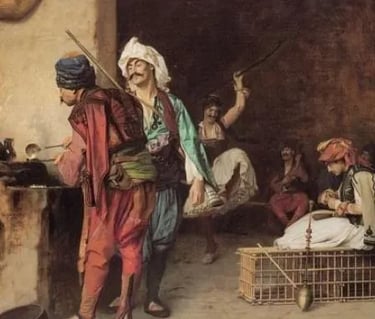

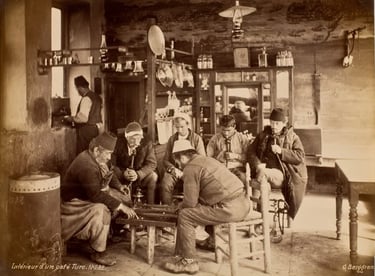

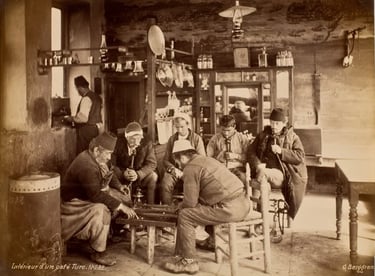

In the 16th century, coffeehouses started to appear in Istanbul. According to sources, the first coffeehouse was opened in Tahtakale. Hakem from Aleppo and Şems from Damascus brought coffee to Istanbul and quickly opened the city’s first coffeehouse in the Tahtakale neighborhood. Coffee rapidly gained popularity both in the palace and on the streets. Coffeehouses became new centers of conversation, literary debates, and social life.

By the end of the 16th century, there were more than 600 coffeehouses in Istanbul. According to Evliya Çelebi, there was even a coffeehouse in Topkapı Palace for Kösem Valide Sultan, the mother of the Sultan. However, coffee was banned at various times. During the reigns of Murad III, Ahmed I, and Murad IV, coffee was prohibited. We’ll gradually get to the reasons for these bans.

It became so popular that it was consumed everywhere. The French writer Edmondo even mentioned in his account that in Istanbul, there was no need to search for a coffeehouse to drink coffee—if you simply shouted “coffee man,” a coffee vendor would appear and bring you coffee on the spot.

Coffeehouses varied structurally. For example, in the summer, it was possible to drink coffee in a coffeehouse along the Bosphorus. There were also winter coffeehouses, mobile ones, and those with lodging facilities.

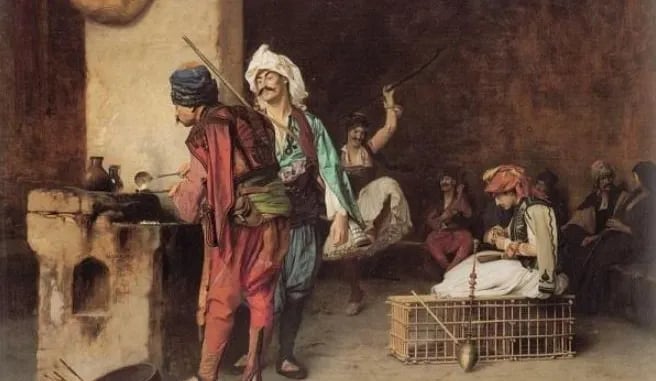

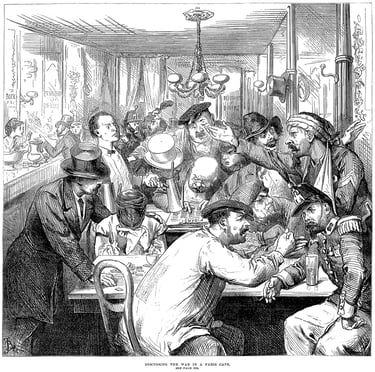

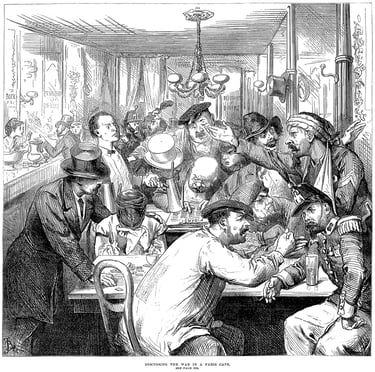

These places brought together people from different backgrounds. They socialized. As is still the case today, Turkish coffee served a purpose and a culture. Janissaries would go there, poets would go there, and ordinary people would go too.

And what did they do? They played games like backgammon and chess, and they talked. They talked about politics, for example. They discussed the Sultan, they voiced their opinions on political stances they disagreed with in the Ottoman Empire. Social ideas, economic conditions, intellectual discussions—all of these took place in coffeehouses.

One of the main reasons for the coffee bans was precisely this. Another reason was the debate on whether the stimulating effect of coffee was religiously permissible. There was a period when coffee was banned on the grounds that, in Islam, consuming something roasted to the point of being “burnt” was considered haram.

Although some saw coffeehouses as a threat, they did not disappear. Even though the reasons for the bans varied from period to period, coffee ultimately became integrated into society.

Coffee was banned multiple times for different reasons because people refused to give up a beloved habit for hundreds of years. In other words, they did not abandon their coffee culture. Official sources mention that coffee was banned or portrayed as something negative many times—whether for political or religious reasons. And not only for religious reasons; in some societies around the world, coffee was also occasionally banned on the grounds that it was harmful to health.

Over time, people grew accustomed to it, and coffeehouses became a new form of social interaction among the public. People of all ranks could enter and socialize without class distinctions. Coffeehouses served many functions, not just as social gathering spaces.

Did you know that the first coffeehouse in Britain was opened in London by a Turk? When coffee first arrived, it was viewed with suspicion because it came from the East. There was a significant taboo and resistance to it—so much so that the resistance even led the King to shut down coffeehouses. However, over time, attitudes toward Turkish coffee softened. What happened afterward is another detailed story.

Returning to Istanbul—

What else happened in coffeehouses?

Traditional shadow plays such as Karagöz and Hacivat were performed there. Theatrical performances and musical recitals also took place. Tobacco was smoked, and hookah became a beloved companion to coffee.

According to one article I read, books, magazines, and newspapers were sold and read in coffeehouses, and if this was the case, they were also called kıraathane (reading houses). It is also said that Sultan Suleiman commissioned history books to be written specifically to be read in coffeehouses.

Over time, coffeehouses reached their golden age—they became vibrant spaces frequented by intellectuals and some of the most important figures in Turkish literature, where even foreign magazines could be found.

Neighborhood coffeehouses also emerged over time, becoming informal administrative decision-making hubs for their local communities.

They were not only centers of politics but also of literature and music. In coffeehouses where folk poets gathered, being a poet was a valued skill, and the heads of these gatherings were even paid salaries by the state.

Janissary coffeehouses developed their own distinct culture. Starting in the 17th century, when Janissaries began to marry, coffeehouses became their social centers in civilian life.

Symbols of their orta (military unit)—such as ships, swords, or fish—were hung at the entrance. It even became a tradition to gift a canary to new coffeehouses for good luck.

These spaces, however, were for men only.

What about women?

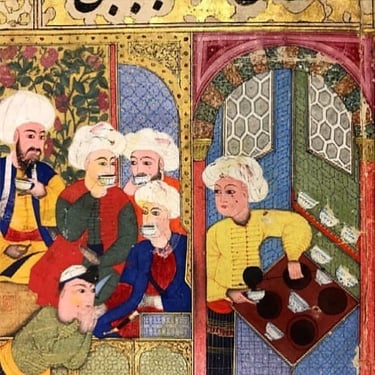

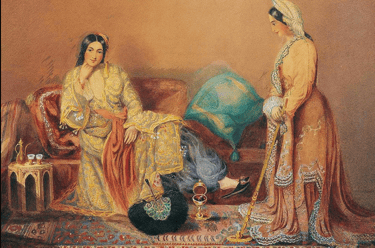

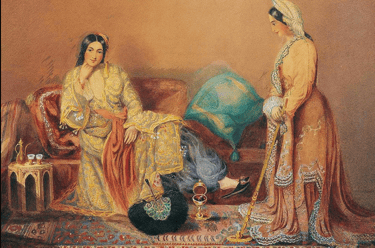

All the coffeehouse images or miniatures you’ve seen depict men, because until a certain period, men and women did not drink coffee together. Coffeehouses were exclusively male spaces. Women, on the other hand, would gather in bathhouses (hamams) or in their homes to drink coffee. Access to coffee for women was considered a real necessity.

Some sources even state that “if a husband refused to buy his wife coffee, it could be considered grounds for severe discord and even divorce.”

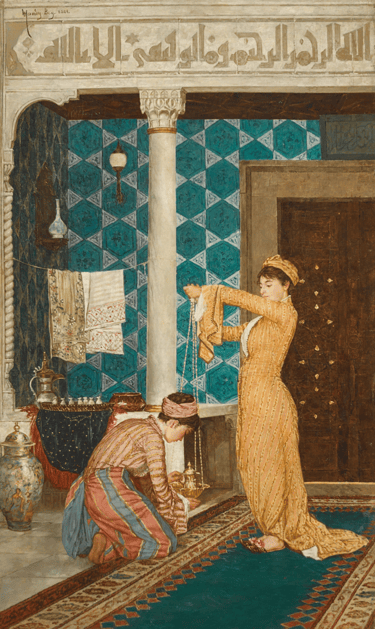

In the palace, there was a designated person responsible solely for coffee. Serving coffee during ambassadorial receptions was one of the symbols of Ottoman hospitality, and presentation was of utmost importance. Coffee sets were ornate and decorative.

In the harem—the private section of the palace where women lived and received their education—coffee was one of the most beloved beverages of the women. However, at first, when coffee was still rare, it wasn’t easily accessible. Think of it this way: when coffee first arrived, it wasn’t something commonly found. It was new, rare, and expensive—a luxury beverage. As its trade and production expanded, coffee gradually became more widespread and affordable. Considering the patriarchal nature of the society, it’s no surprise that this structure strongly influenced women’s access to coffee.

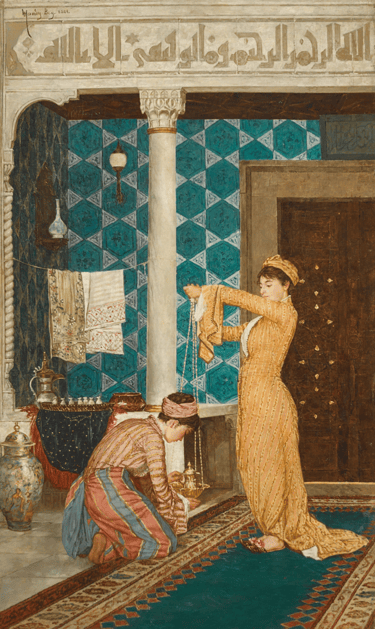

Preparing and serving coffee in the harem followed a strict ceremonial order: Specially trained concubines would prepare the coffee and serve it in cups inlaid with silver and emerald. This ceremony reveals that coffee in the harem was more than just a drink—it was a symbol of status.

Outside the harem, many sultans were also known to love coffee and consume it frequently. By the late 17th century, coffee had already become a standard form of offering. Before official meetings, state guests would be served coffee. The trays and cups used for coffee service were elaborate—golden trays decorated with precious stones. It’s even recorded that coffee was served at the wedding of Sultan Ahmed III’s daughter, right after the ceremony.

The number of palace staff responsible for coffee grew over time. By the early 19th century, the Sultan’s mother alone had three coffee servants. In wealthy households, this number could reach up to seven people responsible for coffee service. One of the main reasons was to display wealth to foreign guests.

What makes Turkish coffee different from others?

Turkish coffee uses Arabica beans—especially those of Yemeni origin.

What makes it unique is the fineness of the grind and the brewing method.

The coffee is ground extremely finely—almost like flour.

It’s medium roasted.

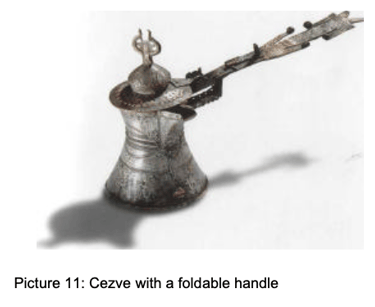

It’s cooked slowly in a cezve (a small long-handled pot) with water and sugar (optional), heated until a foam rises to the surface—but not boiled.

It’s served with a glass of water (to cleanse the palate) and small sweets like Turkish delight.

A proper Turkish coffee must be foamy; coffee without foam is considered carelessly made.

It’s a drink that’s brewed slowly and sipped slowly.

At the beginning, the mixture is stirred once, then left untouched to allow the foam to form.

Turkish coffee has its own special cup, called a fincan. Once poured, the coffee grounds settle at the bottom of the cup—this sediment is called telve.

During the Ottoman period, these cups were decorated with special stones and intricate designs. Even when the outside was colorful, the inside was usually white—because afterward, people would sometimes read fortunes from the cup.

Fortune telling has existed in many forms throughout history, and while it’s not clear exactly when coffee fortune tellingbegan, it’s believed to have emerged during a time when coffee was no longer banned and had become widespread in the Ottoman Empire.

Coffee is drunk → Traditional Turkish coffee with grounds is prepared; once the coffee is consumed, grounds remain at the bottom of the cup.

The cup is closed → After drinking, the cup is turned upside down onto the saucer.

When the cup is closed, objects like rings, keys, or coins are placed on top.

It is left to cool →

The fortune is read → Once opened, the coffee grounds inside the cup are interpreted by turning their shapes into symbols using imagination.

Binding intentions: Ring → love/marriage; Key → new job, new home; Coin → abundance. In other words, the object represents the intention of the person whose fortune is being read.

Energy transfer belief: It is believed that the object “transfers the energy of the person to the coffee grounds.

According to traditional belief, if the cup is turned towards the heart (the chest), matters of the heart (love and emotions) are prioritized. If it is turned outward (facing forward), the reading focuses more on business, travel, money, and worldly matters. A wish is made when the cup is closed. That’s why turning the cup is not just a technical action, but also a ritual that directs the wish.

Of course, rituals and meanings may vary from region to region. By looking at the shapes formed by the coffee grounds, people make predictions about the future. For example: “I see a bird — a journey awaits you soon.” Most of these interpretations are framed in a positive way. In essence, it is a way to strengthen communication between people and spark conversation. It also boosts the morale of the other person. It’s time you set aside to chat, to offer hospitality to guests. In Turkish engagement ceremonies, the bride makes coffee for the groom and adds salt to it. If he can finish it, it symbolically means he is approved.

Today, you can find coffee almost everywhere in Turkey. If you enter a shop, you will usually be offered either Turkish tea or Turkish coffee. The same goes for restaurants after a meal. Even in hair salons, you’ll be offered coffee. You can find Turkish coffee in Starbucks in Turkey. If you visit someone’s home, they’ll offer you coffee. Any café you sit in will serve Turkish coffee. Coffeehouses still exist today as a traditionally male-dominated space. In many societies, coffee has been used as a means of gathering and communication. Coffee fortune telling can actually be seen as a kind of social strategy. Rather than believing or not believing in fortune-telling, it is an enjoyable activity that creates a bond in the meantime. As the Turkish saying goes: “Don’t believe in fortune-telling, but don’t go without it either.”

We know that fortune-telling emerged in the Ottoman Empire after a certain period. There were professional fortune-tellers, too. Palm reading, water divination, and star reading were already practiced. The tradition of Turkish coffee fortune-telling is thought to have originated mostly among women during the 17th century in domestic gatherings, later becoming widespread. Some sources emphasize that the interpretation of the coffee grounds after drinking coffee in the Ottoman period is connected to the method of tasseomancy / tasseography — in other words, coffee reading is a version of the broader tradition of fortune-telling.

For example, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (the wife of the British ambassador living in Istanbul in 1717) mentions in her letters that Turkish women drank coffee in bathhouses. She even described the bathhouse as the women’s coffeehouse. She does not mention fortune-telling, however. According to some accounts, when Hürrem Sultan first tasted coffee, she found its flavor strong and began drinking it with Turkish delight to balance the bitterness. Over time, she preferred melting the delight in the cezve (coffee pot) and mixing it into the coffee. This special recipe was called “Hürrem Sultan coffee” and gradually spread from the palace to the public. However, this information does not come from an academic source.

In 2013, Turkish Coffee was inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List, securing its place as a global cultural treasure.

There are also different varieties of Turkish coffee that you can taste. You can order Turkish coffee plain (sade), medium sweet (orta), or sweet (şekerli). However, the most classic one you can drink is plain Turkish coffee. It is served with Turkish delight and water. The accompaniments and presentations vary depending on the region and the type of coffee.

There are around 40 known types of Turkish coffee.

2. Flavored or Enhanced Varieties:

Dibek Coffee: A coarser coffee obtained by pounding the beans in a stone mortar.

Menengiç Coffee: Made not from coffee beans, but from the fruit of the menengiç (terebinth) plant. It is caffeine-free.

Mastic Coffee: Especially popular in the Aegean region, adding a light aromatic flavor to the coffee.

Süvari Coffee (or Tarsus Coffee): Served in a larger cup than usual, more diluted.

Chickpea Coffee: Made by grinding roasted chickpeas, caffeine-free and mildly aromatic.

Datça Almond Coffee: A special almond-flavored coffee made by blending ground Datça almonds with coffee.

Kenger Coffee: Made by roasting and grinding the seeds of the kenger plant, with a slightly bitter traditional flavor.

“Yandan Çarklı” Turkish Coffee: A foamy Turkish coffee brewed in a special way so that the grounds swirl in the cup.

Black Cumin Coffee: Made by grinding black cumin seeds and mixing them with coffee, known for its sharp aroma and health benefits.

Cilveli Coffee: A showy coffee unique to Manisa, served with sugar or cinnamon sprinkled on top.

Hilve Coffee: A method known in the Arab regions during the Ottoman period; prepared with a simple, light cooking technique.

Mardin Dibek Coffee: A local coffee made by mixing stone-pounded beans with aromatic ingredients such as menengiç, cardamom, and carob.

Tatar Coffee: A Central Asian variety prepared by boiling, without grounds, and usually made with milk.

Lavender Turkish Coffee: Prepared by adding lavender to Turkish coffee, giving it a floral and refreshing aroma.

Saffron Turkish Coffee: Made by adding saffron to Turkish coffee, notable for its golden color and lightly spiced aroma.

Zingarella Coffee: A special Ottoman coffee from the 19th century, served especially in theaters, enriched with syrup, mastic, or various flavors.

Dağdağan Coffee: A traditional Anatolian alternative made from the fruit of the Dağdağan tree.

Mırra: A very strong and dense coffee from Southeastern Anatolia and Arab culture, boiled several times to concentrate it.

Syrupy Coffee: A traditional Ottoman coffee prepared by brewing coffee in sugary syrup, giving it a sweet aroma.

Varieties by Brewing Method:

Brewed in a cezve: The most well-known classic method.

Ember-brewed Turkish coffee: Slowly brewed over hot embers, resulting in a richer aroma.

Sand-brewed Turkish coffee: Brewed in a cezve buried in hot sand, creating thick and long-lasting foam.

Ash coffee: The old method of slowly brewing in the ashes of the fire, giving a lightly smoky flavor.

Different Uses of Turkish Coffee:

Turkish coffee is not only consumed as a beverage but is also used for various other purposes.

If you go to a restaurant in Turkey and a bee approaches your table while you’re dining outdoors, you can ask the staff to burn some coffee. They will bring a small bowl with coffee inside and set it on fire — the smoke drives the bee away.

Additionally, coffee grounds are used as a natural peeling scrub. It is also said that squeezing lemon onto coffee and eating it can stop diarrhea. However, this is not scientifically proven; it is simply a common belief among people.

So, what’s your favorite type of coffee? Do you like Turkish coffee? Do you know any other ways it’s used? Do you have a personal coffee ritual? Don’t forget to share your thoughts. For those who want to read more in depth, are curious about history, or are looking for sources on this topic, I’ve included a comprehensive reference list below. I hope you find it helpful.

don't forget to watch my video and share your opinion ❤️

Referanslar;

Suraiya Faroqhi, Osmanlı’da Gündelik Hayat (Alfa, 2009).

Boğaç A. Ergene, Local Court, Provincial Society and Justice in the Ottoman Empire (2003).

Madeline Zilfi, “Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East” üzerine makaleler.

Preparing coffee: Orientalist art: 2025. Sotheby’s. (n.d.). https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2025/orientalist-art-l25100/girls-preparing-coffee

Tunç, S. (2025b, July 9). Women preparing coffee: Osman Hamdi Bey’s reverse portrait of Orientalism. Daily Sabah. https://www.dailysabah.com/arts/women-preparing-coffee-osman-hamdi-beys-reverse-portrait-of-orientalism/news

Ntv. (2018, February 17). Dolmabahçe Sarayı’nda Bir ilk. NTV Haber. https://www.ntv.com.tr/galeri/turkiye/dolmabahce-sarayinda-bir-ilk,BPEBM4L31kapHoIgpdLbAg/T_yfjCNEZ0iLVixggAxVpg

F., N. (2018, February 23). Eski Osmanlı Kahvehaneleri Fotoğraf galerisi. Tarih Kurdu. https://tarihkurdu.net/osmanli-kahvehaneleri-fotograf-galerisi.html

HistoryMaps. (n.d.). First Coffee House in Venice. HistoryMaps. https://history-maps.com/story/Republic-of-Venice/event/First-Coffee-house-in-Venice

Kayayerli, D. (2015, August 18). Istanbul’s old coffeehouses offer tranquility to visitors. Daily Sabah. https://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2015/08/19/istanbuls-old-coffeehouses-offer-tranquility-to-visitors

Tarihi Mekanlar Kişisel Ansiklopedi Erol şaşmaz. (n.d.). https://www.turkiyenintarihieserleri.com/?oku=517&

Beta Yeni Han 1554 coffee museum • location, photos and information • cultural inventory. Kültür Envanteri. (2025, September 27). https://kulturenvanteri.com/en/yer/beta-yeni-han-1554-kahve-muzesi/#15.17/41.018743/28.970797

Turkish coffee, not just a drink but a culture. The UNESCO Courier. (n.d.). https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/turkish-coffee-not-just-drink-culture

Kuzucu, Kemalettin. “YILDIZ SARAYI’NDA KAHVE”. Milli Saraylar Sanat Tarih Mimarlık Dergisi, sy. 27 (Aralık 2024): 99-111.

Turkish embassy letters: Turkish Embassy Letters. Turkish Embassy Letters | Turkish Embassy Letters | Manifold @CUNY. (n.d.). https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/turkish-embassy-letters/section/11a140f8-d4a3-4ae7-8832-37f4bb906d7f

Yılmaz, B., Acar-Tek, N., & Sözlü, S. (2017). Turkish cultural heritage: A cup of coffee. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 4(4), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2017.11.003

Açıkgöz, C. (2022). Kahvecibaşı Nakşî Mustafa Ağa’nın (ö. 1764) hayatı, Eserleri ve Edebî Kişiliği. Trakya Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 12(24), 199–234. https://doi.org/10.33207/trkede.1085833

Özdem, F. (2009). Karaların ve Denizlerin Sultanı İstanbul: Cilt II. İstanbul: Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık.

Samancı, Ö. (2008). Alaturkadan Alafrangaya: 19. yüzyılda Osmanlı saray mutfaklarında kullanılan araç ve gereçler. In A. Bilgin & Ö. Samancı (Eds.), Türk mutfağı (pp. 307–325).

Alagözlü, N. (2007). An analysis of coffee cup reading as a discourse genre: Fortune telling with coffee and ideology. Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi / Journal of Faculty of Letters, 24(1), 1–22.

Kucukkomur, S., & Ozgen, L. (2009). Coffee and turkish coffee culture. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 8(10), 1693–1700. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2009.1693.1700

Çetin, Ö. H., & Çelik, E. Ü. (2020). Elbise-i atika-i osmaniye. History Studies International Journal of History, 12(6), 3307–3331. https://doi.org/10.9737/hist.2020.967

Tarım, Z. (2015). Osmanlı Devlet Teşrifatında Kahve İkramı. In E. Pekin (Ed.), Bir Taşım Keyif: Türk Kahvesinin 500 Yıllık Öyküsü (pp. 199–215). Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınları.

Can, M. A. (2018). Osmanlı toplumunda kahve ve kahvehaneler (Unpublished bachelor’s thesis). Bartın Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Tarih Bölümü.

Demir, Y., & Bertan, S. (2023). Spatial distribution of Türkiye’s local Turkish Coffee Kinds. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-023-00200-8

ÇAPAR İLERİ, S. (2020). The analysis of the importance of Turkish Coffee and coffeehouses with the comparison between British and Ottoman culture. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 392–397. https://doi.org/10.29000/rumelide.814324

Erdoğdu, A., & Gedük, S. (2015). Çin porseleni fincanlar. In E. Pekin (Ed.), Bir taşım keyif: Türk kahvesinin 500 yıllık öyküsü (pp. 283–301). Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi.

ÇELİK YEŞİL, S., & YILDIZ, S. (2024). 17. yüzyıl i̇stanbul Mutfağına 1640 tarihli narh Defterinden Bir Bakış (a look at the 17th century Istanbul Cuisine from the Narh book dated 1640). Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies. https://doi.org/10.21325/jotags.2024.1389

Tasty Tools

Explore gastronomy.

Concact:

© 2025. All rights reserved.