The Origin and History of Turkish Tea

Discover the fascinating history of Turkish tea, from its arrival in Turkey to what makes it unique compared to regular tea. Learn how to brew the perfect cup of Turkish tea and explore regional differences and the cultural significance of this beloved beverage.

10/13/202512 min read

The origin of the word “tea”

The earliest history of tea

The arrival of tea in Turkey

What makes Turkish tea different from regular tea?

Tea glass

How to brew tea

Smuggled tea

Regional differences

Tea is not just a beverage; in Turkey, it is an inseparable part of social life, hospitality, and daily rituals. From morning breakfasts to evening conversations, tea accompanies every moment of our lives and represents a cultural as well as economic heritage. But how did this drink, which has become a symbol of Turkey, emerge, what historical processes did it go through, and how does Turkish tea differ from other types of tea? In this article, we embark on a comprehensive journey through the history of tea, its production methods, tea culture, and consumption habits.

The Etymology of “Çay” (Tea):

Tea is a part of daily life for millions of people around the world today. But it’s not only the leaves that have traveled across continents—the word itself has taken a long linguistic journey. The Turkish word “çay” carries a layered story of transmission that starts in China and extends through Mongolian, Turkic, Russian, and various European languages. This etymological journey also reflects the cultural exchange networks of the Silk Road.

The homeland of tea is China, and the Chinese character for tea, 茶 (cha), is pronounced in two distinct ways:

Cha (Mandarin Chinese and northern dialects)

Te (Min Nan dialect, especially Fujian region)

These two pronunciations correspond to two historical routes through which tea spread to the world:

Overland Route – the “Cha” Route:

As tea traveled via overland trade routes through Central Asia, Persia, Ottoman lands, and Russia, names derived from the “cha” pronunciation were adopted. The Turkish “çay,” Russian “чай (chai),” and Persian “čây” all stem from this route.Maritime Route – the “Te” Route:

Through maritime trade from China’s southern coasts, tea spread to Western Europe, particularly via the Dutch and the English. On this route, the Fujianese pronunciation te was adopted. Words like English tea, French thé, and German Tee come from this path.

These two linguistic routes show how tea journeyed across the world in both geographical and cultural senses, shaping languages and trade alike.

Transmission into Turkish via Mongolian:

The Turkish word “çay” did not come directly from Chinese, but through Mongolian. While the Mongols were in contact with the northern regions of China, they adopted the word for tea in the form “çai / tsai.” From the 13th century onward, this form spread across Central Asia and entered the languages of Turkic-speaking communities as “çay.”

This process was not merely a linguistic transfer; it was also the result of the intense trade and cultural exchange between East and West during the era of the Mongol Empire.

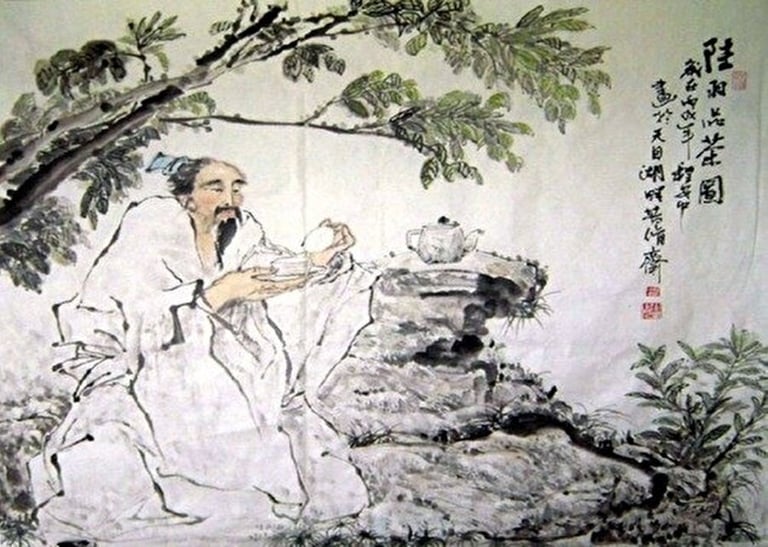

A Thousand-Year Journey Beginning in China:

The earliest known history of tea traces back to China. According to legend, in 2737 BCE, while Chinese Emperor Shen Nung was boiling drinking water, a few leaves were carried by the wind and fell into the pot. The aromatic drink that emerged pleased the emperor and thus, tea was discovered.

Historical records show that tea was an important part of trade in Asia since ancient times. In the 9th century, Arab travelogues mention that the revenues of Canton (Guangzhou) came from tea and salt. Thanks to the Silk Road, tea reached Ottoman lands long before it ever arrived in Europe.

Early Traces in Ottoman Lands:

Although tea reached Ottoman territories quite early, it took time for it to become a widespread beverage. Evliya Çelebi’s travelogues and customs records confirm the presence of tea in the empire. Documents from 1777 and 1816 indicate that tea was being imported, while the first treatises on tea, published between 1872 and 1883 in Istanbul and Cairo, are recorded as the earliest Turkish-language tea books.

Initially, tea leaves were used for medicinal purposes within limited circles. During the 19th century Tanzimat period, tea began to appear at breakfast tables and in social spaces. The 1878 Trabzon yearbook notes that 20,000 kıyye (an old weight unit) of tea were produced in the Hopa district a significant record showing that local tea production had started in the Eastern Black Sea region.

Official records also reveal that tea-like plants were being grown in gardens and forested areas around Trabzon and Rize, that locals earned income by selling them, and that the state collected taxes from these products. In other words, tea’s journey in Anatolia began with the interest and initiative of the local people.

State Initiatives and Early Experiments:

In 1888, Hasan Fehmi, the district governor of Mudanya, mentioned tea seedlings brought from China. The Ministry of Forestry collected samples to examine the plant’s potential health benefits and harms. Reports sent to the palace highlighted tea’s “nutritious and healing properties” and recommended importing seeds and seedlings from Japan.

During the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, these recommendations were taken seriously. Following a report presented by Selim Pasha, the Minister of Forestry, Mines, and Agriculture, tea seeds were imported from Japan, and experimental plantings were carried out in various regions from Trabzon to Bursa. This initiative marked one of the first planned steps of the Ottoman Empire toward tea cultivation.

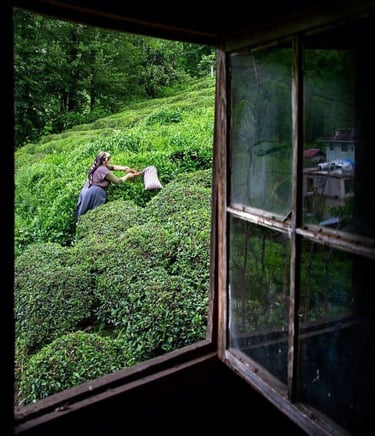

The Beginning of Modern Tea Cultivation in Rize:

At the beginning of the 20th century, Hulusi Bey, the president of the Rize Chamber of Agriculture, brought tea seeds from Batumi and conducted planting experiments in his own garden. However, wars and the Russian occupation interrupted these efforts. In 1918, Ali Rıza Bey was sent to Batumi to study the climate and soil conditions. He scientifically reported that the Black Sea region was suitable for tea cultivation. These reports became the first serious scientific studies shaping the future of tea in Turkey.

Zihni Derin and the Republican Breakthrough:

Under the leadership of the Republic’s agricultural and economic development policies, prepared in line with Atatürk’s vision, tea-related initiatives gained momentum. At this point, Zihni Derin stepped in as a key figure working within the framework of these policies and actively involved in the tea project.

After World War I, the economic difficulties in the region made the creation of new agricultural areas a necessity. In 1921, a commission established in Ankara brought up the issue of tea production in Rize. Zihni Bey (Zihni Derin), the Director General of Agriculture, went to the region and led the establishment of nurseries. In 1924, a law was enacted to formalize these efforts, transforming tea production from individual initiatives into a structured state project. In the 1930s, tons of seeds and thousands of seedlings were imported from the Soviet Union to expand cultivation.

Tea Law, Factories, and Expansion:

In 1938, 135 kilograms of tea leaves were produced, yielding 30 kilograms of dried tea, which was sent to Ankara. On March 29, 1940, Law No. 3788 on Tea was enacted, legally securing and supporting tea cultivation. The coastal strip from the Araklı River in Trabzon to the Georgian border was declared a tea cultivation area, and interest-free loans were provided to producers through Ziraat Bank. In the early 1940s, the trade of tea and coffee was brought under state monopoly. The Rize Tea Factory, whose foundations were laid in 1946, began production in 1947. This factory also paved the way for Turkey’s tea exports.

ÇAYKUR and a New Era with the Private Sector:

In 1971, tea-related authorities were centralized under a single structure. With the establishment of ÇAYKUR, the sector developed rapidly. A new era began in 1984 when Law No. 3092 allowed private sector participation in tea production. As a result, production tripled, and tea became a new source of livelihood for the people of the Black Sea region.

Today, 65% of tea-growing areas are located in Rize, 21% in Trabzon, 11% in Artvin, and the remaining small portion in Giresun and Ordu.

First Tea Factory in Türkiye

Zihni Derin

Is Black Tea Actually Green?

Let’s start with a basic botanical fact: all “true teas” in the world (black, green, white, or oolong) come from the same plant, Camellia sinensis. The difference lies in how the leaves are processed, particularly in the degree of oxidation. It’s often mistakenly referred to as “fermentation,” but the correct term is oxidation.

Green tea is heated right after harvesting to deactivate the enzymes, preventing oxidation and preserving its natural green color. Black tea, on the other hand, undergoes full oxidation. The leaves are withered, rolled, and exposed to oxygen, which turns them dark and develops their characteristic aroma and flavor. Turkish tea is produced using this second method (full oxidation) so it belongs to the black tea category.

Processing of Turkish Black Tea:

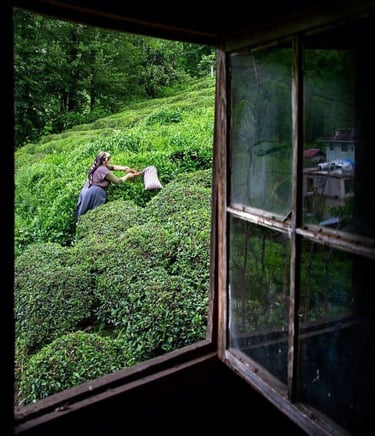

Harvest (May–October): The top two leaves and the bud of the tea shoots are hand-picked or cut with shears. In Turkey, there are usually 3–4 harvest periods each year.

Withering: Fresh leaves are spread out on large trays in factories and exposed to heated air until they lose about 70% of their moisture.

Rolling: The leaves are rolled to break their cell walls, allowing enzymes and juices to react with oxygen. This stage shapes the tea’s aroma.

Oxidation (often called “fermentation”): The rolled leaves are left to rest for 2–3 hours at a controlled temperature (20–25 °C). This is when black tea’s distinctive color and flavor develop.

Drying: Oxidation is stopped by heating the leaves to 90–100 °C, extending shelf life.

Sorting & Packaging: The dried tea is sifted to separate different leaf sizes and then packed.

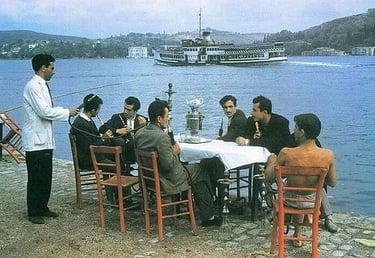

The Spread of Tea in Turkey and the Rise of Tea Gardens:

In the beginning, tea was seen as an alternative or complementary beverage. Its presence in coffeehouses and daily life accelerated from the late 19th century onward, especially during the Republican era.

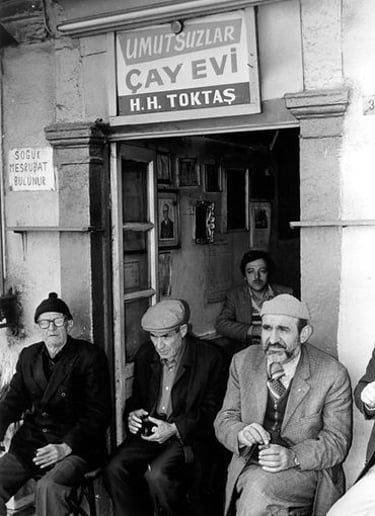

In the 19th century, coffeehouses were the social hubs of the Ottoman Empire, where people drank coffee, conversed, and strengthened social ties. Tea entered Turkish social life later than coffee. As consumption grew, it became common not only at breakfast tables but also in coffeehouses.

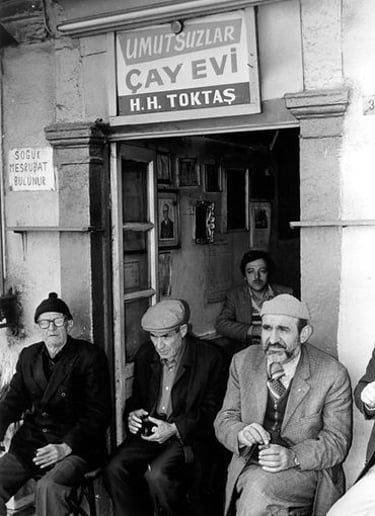

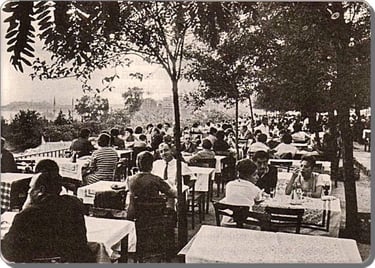

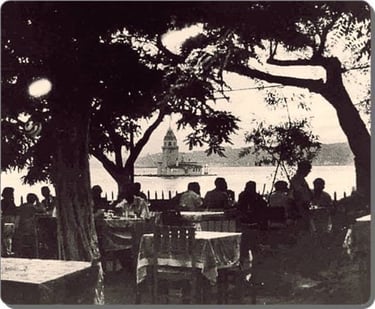

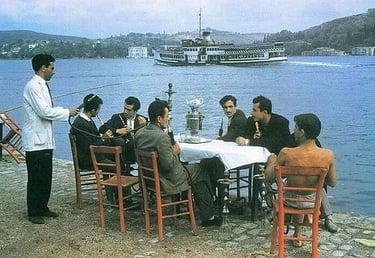

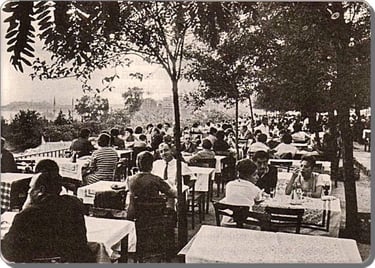

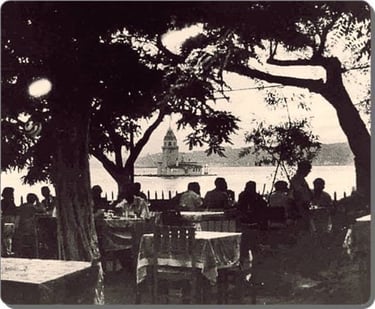

From the 1950s onward, “tea gardens” and “tea houses” dedicated to tea drinking began opening in major cities. Seaside areas, parks, and scenic spots naturally became their favored locations. These spaces turned into symbols of conversation, leisure, and slowing down.

One of the main reasons tea was so easily embraced as an alternative to coffee is its drinkability. Turkish coffee is strong and due to its high caffeine content, it’s typically consumed in limited amounts. Tea, however, can be enjoyed cup after cup, extending conversations a beloved habit in Turkish culture.

The Turkish Tea Glass: Why This Shape?

Although the exact history of the traditional Turkish glass for tea is not fully known, its logic is crystal clear. Because it’s made of glass, you can easily see the strength of the brew and understand how intense the tea is. Scientifically, it has been proven that the material of food and drink containers affects taste; the same tea tastes different when you drink it from a mug. Just like wine, tea has its own special glass.

So why is it thin-waisted? Its design is ingeniously practical: the bottom is wide so it can hold more tea, the middle part is narrow so it cools more slowly, and the top is wide for comfortable drinking. Choosing a tea glass is a personal preference, everyone has their favorite style.

How Is Tea Brewed?

The essential tool for brewing tea is the çaydanlık, a double-stacked teapot. We don’t know exactly who invented it, but its practicality is undeniable: the bottom part boils water, while the top is used for steeping the tea. The word dem comes from Arabic, meaning “blood,” and from Persian, meaning “breath” or “time.” Turks call perfectly brewed tea tavşan kanı(“rabbit’s blood”), so the “blood” meaning makes sense too.

The brewing process is simple but entirely based on intuition. First, water is boiled. Then, the desired amount of tea is added to the upper pot. If you don’t want your tea to become cloudy, you can rinse the leaves beforehand. Since the water in the bottom pot stays at a simmer, the brew remains hot. Techniques vary from person to person: some start with cold water, others add water first then tea, and some like to mix different brands.

Smuggled Tea:

Smuggled tea entered Turkey mostly by land through the Iranian border and from former Soviet countries, especially Georgia. Among the public, it was commonly known as Acem Çayı (Persian Tea) or Tırç.

Why Was It Preferred?

High Taxes and State Monopoly: Before the 1980s, tea production and sales were under state monopoly, and high taxes made legal tea expensive.

Price Difference: Smuggled tea was significantly cheaper than local tea, as it came from neighboring countries at much lower prices.

Some people even became so accustomed to its taste that they continued to prefer smuggled tea even after legal tea prices dropped.

Turkey = The World’s Biggest Tea Drinker:

Turkey ranks number one in the world in per capita tea consumption. According to FAO and international tea committee data, annual per capita tea consumption in Turkey exceeds 3.5 kg, which corresponds to about 3–4 glasses of tea per day.

Academic studies emphasize that in Turkey, tea is more than just a beverage, it’s a social connector. Inviting someone with “Come, have a glass of tea” builds social bonds; long conversations, workplace breaks, and even formal meetings often happen over tea. This deep cultural intertwinement is one of the key factors that makes Turkey the world champion in tea drinking.

Regional Differences: With Lemon or Plain

Although adding lemon to tea is common throughout Turkey, it’s particularly prominent in Eastern Anatolia and the Eastern Black Sea regions. There are two main reasons for this:

British Influence in the Ottoman Era: In the 19th century, through Ottoman–British relations, lemon tea first became popular among the palace and elite circles, and later spread to the general public.

Taste and Health: Lemon balances the tannins in tea, giving it a smoother flavor. Additionally, its vitamin C content and immune-boosting properties contributed to the local adoption of this habit.

Although its history isn’t as old as coffee’s, tea quickly became beloved and an indispensable part of Turkish culture.

Thanks to Zihni Derin and other patriotic figures whose names we do not know, today the Black Sea region has become a significant source of income. Turkish culture now has its own tea brand. Following the path opened by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, important people like Zihni Derin were able to take actions beneficial to the nation, and thus Turkey gained a valuable legacy. For every cup of tea we drink and every conversation enjoyed alongside it, we should know and remember these people more. In honor of Zihni Derin, with respect…

References:

Clauson, G. (1972). An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth-century Turkish. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bretschneider, E. (1871). On the knowledge possessed by the ancient Chinese of the Arabs and Arabian colonies. London: Trübner & Co.

Mair, V. H. (1998). Language and script in the Chinese world. In D. Twitchett & M. Loewe (Eds.), The Cambridge history of China (Vol. 1, pp. XXX–XXX). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mair, V. H. (2009). The true history of tea. London: Thames & Hudson.

Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Tea; cha. Oxford University Press. Retrieved [tarih] from https://www.oed.com

Nişanyan, S. (n.d.). Çay [Madde]. Nişanyan Sözlük. Retrieved [tarih] from https://www.nisanyansozluk.com

Alıkılıç, D. (2016). Çay’ın Karadeniz bölgesi için önemi ve tarihi seyri. Journal of Black Sea Studies, 21, 269–280.

Göde, M. Ö., Sayarı, B. K., & Ekincek, S. (2023). Bir Cumhuriyet dönemi içeceği olarak çayın Türk toplumundaki yolculuğu [The tea’s journey in Turkish society as a republican period beverage]. Journal of Gastronomy, Hospitality and Travel, 6(3), 1233–1252.

Karabağ, A. R. (yıl yok). Beş bin yıllık çay kültürü ve Türkler. Sağlıklı Beslenme ve Gıda Takviyeleri.

YURTOĞLU, N. (2018). Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Nde çay Yetiştiriciliği Ve çay Politikaları (1923-1960). History Studies International Journal of History, 10(8), 209–232. https://doi.org/10.9737/hist.2018.671

Netfotograf(n.d.).Seyyar.Netfotograf.comFoto.https://galeri.netfotograf.com/fotograf.aspfoto_id=381389&sr=9&syf=1596&utm_

Tasty Tools

Explore gastronomy.

Concact:

© 2025. All rights reserved.