Kokoreç: History and The Story Behind It

Discover everything about kokoreç, the delicious street food that has a rich history. Learn what kokoreç is, its cultural significance, and why it's a must-try for food lovers.

10/23/20256 min read

Introduction

The Origins of the Tradition of Cooking with Intestines

Ancient Greek and Byzantine Origins

The Ancient Origins of Stuffed Intestines

From Byzantium to Modern Türkiye

Early Turkish Sources

The Global Use of Intestines

How to Prepare Kokoreç

Did You Know?

Closing

Kokoreç is a staple of late-night dining in Turkey. Eating kokoreç, accompanied by lively music, becomes a delightful adventure for all the senses. However, eating animal innards has a much older history than the streets of Istanbul. For centuries, people have found ways to transform internal organs into delicious dishes.

But have you ever wondered about the origins of this unique dish? Like many traditional dishes, kokoreç has its roots in ancient civilizations and ancient traditions. From Mesopotamia to Egypt, from Rome to Byzantium...

The Origin of the Tradition of Cooking with Intestines:

The use of animal intestines in cooking is as old as the history of meat consumption. In early agricultural societies, people learned not to waste any part of the animal. Intestines were cleaned, filled with spices and grains, and cooked. This was not only a measure of economy but also an example of early culinary creativity.

In ancient Mesopotamia, tablets dating back to 1700 BC contain recipes for stuffing mixtures of minced meat, fat, herbs, and spices into animal intestines. These are the ancestors of modern sausages and dishes like kokoreç and mumbar, and they exemplify the collective gastronomic mindset from the earliest civilizations to the present day.

Ancient Greek and Byzantine Origins:

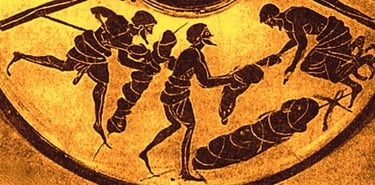

The earliest traces of dishes most similar to modern kokoreç date back to Ancient Greek and Byzantine cuisine:

Ancient Greece: Homer's epics mention dishes in which intestines were cooked on skewers. The Greeks would skewer lamb or goat meat along with offal, and marinate the intestines in vinegar, honey, and water to both cleanse and flavor them.

Byzantine Empire: Dishes very similar to modern kokoreç are documented under the names plektín, koilióchorda, and chordókoila. A smaller version, gardúmpa or gardoumpákia, also dates from the period. Some names are used in modern Greek dialects for stuffed intestines.

The Ancient Origins of Stuffed Intestines:

Mumbar is also a very popular traditional dish in the Middle East and Turkey. Intestines are stuffed and cooked as dolma (stuffed meat). While researching this topic, I realized that in some societies, the tradition of stuffing intestines evolved into sausages, while in others, it evolved into kokoreç (a type of meat called kokoreç).

However, stuffing intestines as food is actually a very old technique. In fact, the Sumerians, and later the Akkadians, stuffed animal intestines and consumed them as food.

Scholars generally refer to this as "sausage"; of course, sausage is a topic for a separate historical text, as the historical processing methods differ. However, because of the use of intestines, I wanted to focus on the way intestines were used as food. If we're talking about the Sumerians, we're going back 5,000 years, and this gastro-collective consciousness is truly impressive, in my opinion. Furthermore, Babylonians have translated recipes and have been observed cooking intestines on tablets currently held in the Yale University archives.

Picture of Mumbar

From Byzantium to Modern Turkey:

By the Byzantine period, we see that dishes similar to kokoreç were clearly present in regional cuisines. In Constantinople, street vendors sold dishes made primarily from offal; simple, delicious, and satisfying dishes. These dishes bore strong ties to both Greek and Roman culinary traditions.

When the Ottoman Empire inherited this cultural mosaic, recipes made with ingredients such as intestines, liver, and offal continued to develop in Anatolian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern cuisines.

Kokoreç, in particular, became one of Turkey's signature dishes, preserved in various interpretations in cities like Izmir, Istanbul, and Ankara. Today, famous kokoreç restaurants are found throughout Türkiye. You can find distinctive kokoreç dishes being made in different Anatolian cities.

Image: “Göbel Kokoreç” Facebook page.

Image: “Göbel Kokoreç” Facebook page.

Early Turkish Sources:

Dîvânu Lugâti't-Türk (11th century): Mahmud of Kashgar mentions yörgemeç, a dish similar to kokoreç. He demonstrates the nomadic Turks' culture of utilizing offal. There are also sources claiming that the history of kokoreç in the Turks is rooted in yörgemeç.

Ottoman Period: Offal was common in Ottoman cuisine, but the term "kokoreç" emerged later.

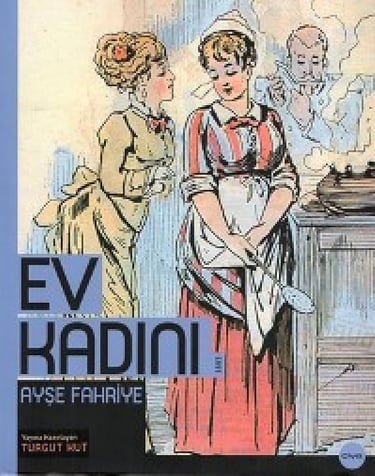

Ayşe Fahriye's book Ev Kadını (Housewife) (1894) contains a kebab recipe titled Kur kureç or Kokoreç.

Ömer Seyfettin's 1920 story Lokanta Esrarı mentions kokoreç, made from small lamb intestines prepared by an Athenian Greek chef in Istanbul. The text contains a dialogue. They say they will bring someone from Athens who knows how to make kokoreç, and he asks what kokoreç is. This means it wasn't yet as popular a dish as it is today. There were people who knew about it, and there were people who knew where to find them. However, given its recent history, we can tell how quickly kokoreç adapted to the culture.

Masters from Erzurum, seeing a shortage in the market, brought these intestines to Izmir and sold them. Previously, these intestines were thrown away. This is how they created the modern Turkish street version of kokoreç, particularly popularizing the Izmir style. They also came to Istanbul and made kokoreç. Combining knowledge from their animal husbandry culture with the resources available in the city market, they transformed kokoreç into a popular street food. These masters from Erzurum learned from their own masters in Erzurum. I don't know where kokoreç came from in Erzurum or if it was already an existing culture.

Global Use of Intestines:

Intestines are widely used in processed meat products such as sausages and salami:

Europe: German Bratwurst, Italian Salsiccia, Spanish Chorizo, English Black Pudding, Scottish Haggis.

Balkans and Turkey: Traditional sausages such as sucuk are stuffed in natural casings. Kokorec (a type of sausage) also exists in the Balkans.

Asia: Many local sausages and delicacies are made using intestines.

How to Prepare Kokoreç:

Modern kokoreç is prepared as follows:

The intestines are cleaned with salt and vinegar.

Fatty liver pieces or other offal are skewered.

The intestines are wrapped around the skewered meat.

The entire skewer is barbecued; sometimes it is pre-cooked and then stored.

After cooking, it is chopped, seasoned with spices such as thyme, cumin, and paprika, and served between bread or on a plate.

Did You Know...?

During Türkiye's accession process to the European Union, kokoreç was deemed a food safety risk, and its ban was debated. This sparked a gastro-nationalist backlash in Türkiye, and people championed kokoreç as a cultural symbol. It became the subject of songs and inspired strong social solidarity. The same thing happened in Greece.

Spread from the Ottoman Empire to the Balkans, kokoreç continues to thrive there today.

So the next time you see kokoreç grilled at midnight… remember: you're tasting history.

References:

İnanöz, K., Özdemir, M. E., & Erdem, Z. (2022). "Türk Kültüründe Kokorecin Tarihsel Serüveni". Anadolu Akademi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 4(1), 19-29. (DOI: 10.51860/anadoluakademi.1091759)

Seyfettin, Ö. (1970). Bütün Eserleri IX, Hikaye Dizisi: 18 (Lokanta Esrarı). Ankara: Bilgi Basımevi.

Gümüş, A. (2019). Tarihten Beslen Gençliğe Sağlıkla Seslen. VI. Uluslararası Tarih Eğitimi Sempozyumu (ISHE 2019)içinde (s. 72-99). Bolu: Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi e-yayınları.

Babiniotis, G. (2002). Lexikó tis Neoellinikís Glóssas (Yeni Yunanca Sözlük). Athína: Kentro Lexikologías.

Kut, G., & Kut, T. (2015). Mehmed Kâmil, Melceü't-Tabbâhin Aşçıların Sığınağı. İstanbul: Türkiye Yazma Eserler Kurumu Başkanlığı Yayınları.

Baycar, A. (2021). Understanding Kokorec through gastro-nationalism and securitization during EU-Turkey membership negotiations. Journal of Interdisciplinary Food Studies, 1(1), Fall 2021. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5791134

Tasty Tools

Explore gastronomy.

Concact:

© 2025. All rights reserved.