History of Akide Candy: From Ottoman Empire to Today

Discover the rich history of akide candy, a traditional Turkish sweet that has roots in the Ottoman Empire. Learn how it is made and its significance in Turkish culture today, along with all the fascinating details about this beloved candy.

11/4/20258 min read

Origin of Sugar:

The origin of sugar dates back to ancient times.

Sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) is native to New Guinea and Southeast Asia. From there, the plant spread to India and then into Asia. In the early days, people chewed the cane stalk to extract its sweet juice—that is, the sugar extract was not crystallized.

The process of sugar crystallization (rafination) was first developed in India around 350 AD.

During this period, the Sanskrit word "śarkarā" (meaning crystallized sugar) came into use, later passing into Western languages as the Persian "shakar," the Arabic "sukkar," and the Latin "saccharum" (Sergy, 2019, p. 3).

He states that after India, knowledge of sugar processing reached the Persian (Sassanid) Empire, where sugar refining was carried out using more advanced production techniques. Beginning in the 7th century, as a result of Arab conquests, sugar production moved to the Middle East, and sugarcane cultivation developed, particularly in regions such as Syria, Egypt, and North Africa.

Sugar was introduced to Europeans during the Crusades (11th–13th centuries). Until then, sugar in Europe had been a very expensive commodity, used like a "medicine" or "spice."

And in the 15th centuries, Venetian and Genoese merchants conducted the sugar trade via the Mediterranean.

With the discovery of America in the 16th century, European colonial powers, particularly Portugal, Spain, France, and England, brought sugarcane production to the Caribbean and the Americas.

The first settlers to the Caribbean began cultivating sugar. This was a new form of production. Slaves worked vast areas. This trade network significantly impacted the global economy. Slaves came from Africa. Most died quickly due to poor living conditions. Sugar was highly valued because it thrived in a specific climate. It was expensive and a symbol of status.

Raw materials from the Caribbean were sent to Europe for processing. This was called the triangular trade. Slaves from Africa went to work in the Caribbean. The raw materials they processed were sent to Europe for processing.

He states that in 1747, German chemist Andreas Marggraf extracted sucrose from sugar beets, but this discovery was transformed into industrial production by Franz Carl Achard (1801).

Sugar could now be produced not only in tropical regions but also in temperate climates.

Regarding the Ottoman Empire, before sugar, sweeteners like honey and molasses were used. Desserts were sweetened with honey and molasses. Sugar then entered our lives. Because it was expensive, sugar, like every new product, first began in the palace. In other words, when sugar first arrived in the Ottoman Empire, it became a luxury for the public. Except for special occasions, the public didn't know the taste of sugar. If it was available in the palace, it was a luxury and a desired sweetener. In the case of sugar, it was considered a luxury due to the manpower-intensive nature of its production, the difficulty of trade, and the fact that the product wasn't grown everywhere, meaning it wasn't yet widely available. However, when sugar arrived, it didn't immediately replace honey in the palace. They didn't just buy it and replace it as a sweetener the next day. This was a process. After a while, it reached the wealthy, and then the general public. Confectioners began to open throughout the city. Trade began to increase. Eventually, honey became a sweetener for those who couldn't afford sugar.

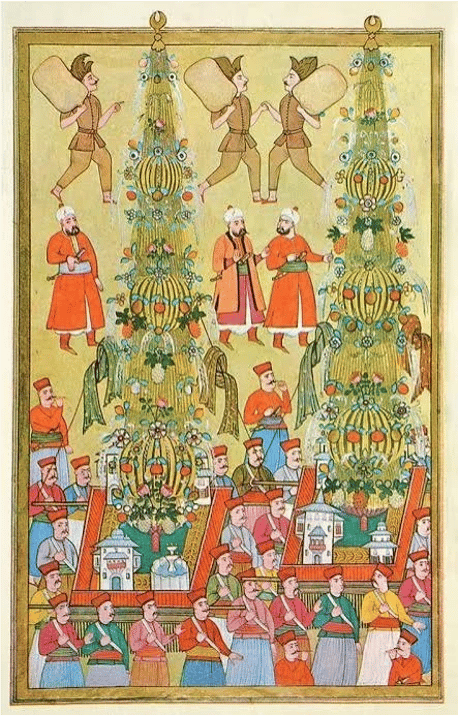

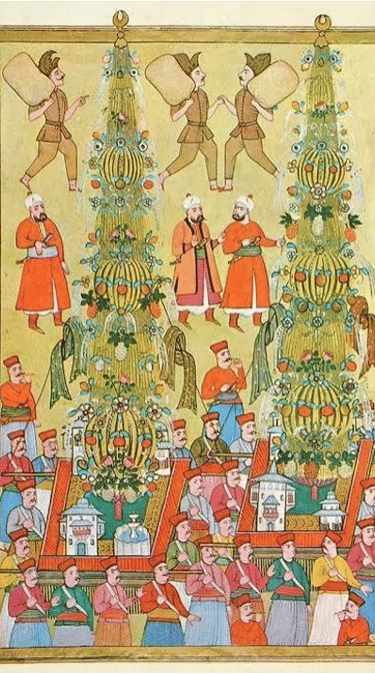

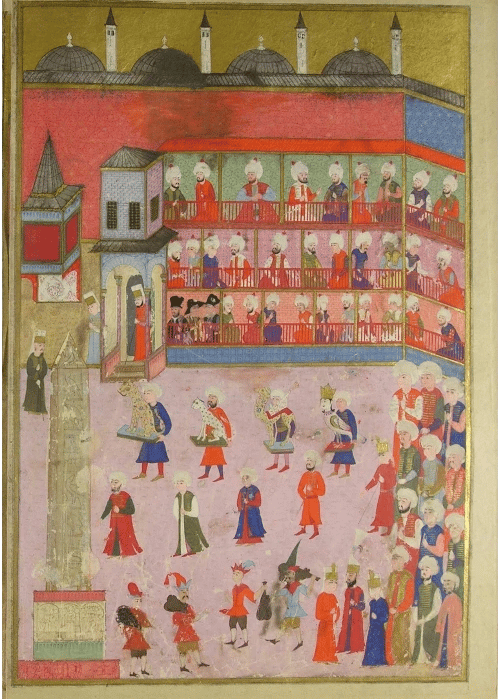

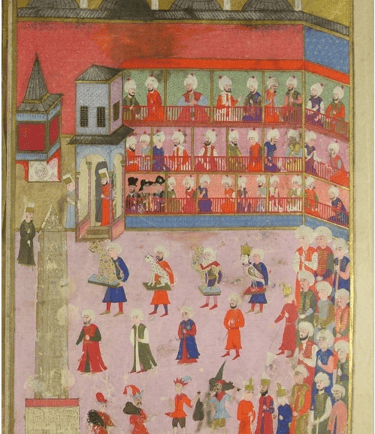

Going back to the 15th-century Ottoman palace, all kinds of fruit were candied and enjoyed. Chestnut candy, which still holds a significant place in Turkey, was also invented during this period. Sugar was so important in the Ottoman palace that there were "Palace Confectioners." These were the artisans who produced sugar for the palace. In other words, the sugar supply came from selected tradesmen. Foods, such as sugar and coffee, were served to more important individuals and on important occasions. They served it abundantly during palace festivals, religious holidays like Ramadan, Nevruz, which celebrated the arrival of spring, the wedding of a member of the sultan's family, and when welcoming foreign delegations. The largest production was in Egypt. They often received orders from the palace, produced it, and shipped it. At festivals, sugar animals and trees were made and displayed, and the public was allowed to plunder them. Thus, the public consumed sugar on special occasions. Miniatures were made from sugar. In other words, there were sugar masters. There were sugar artisans.

The images on the right and below are from various Ottoman celebrations. The wooden figures and animal motifs people carry on trays are not real trees or animals, but rather sugar sculptures.

Sugar stocks were closely monitored in the palace. Sugar was purchased as soon as winter arrived.

Soldiers also placed great importance on this. Sugar was a necessity for the army's pre-campaign preparations. We also know that there was a sugar bazaar in Galata, Istanbul, in the 17th century. It was subject to taxation, and its price fluctuated periodically. Akide was one of the most important examples.

"For example, in 1582, the price of akide rose from 20-30 akçe to 45-50 akçe."

What does this mean?

Considering the end of the 16th century, the estimated average was:

20 akçe ≈ 2 days' wages for a worker, or 1 okka (1.28 kg) of bread → 1-1.5 akçe.

This corresponded to the purchasing power of approximately 13-15 kg of bread.

So, What is Akide Candy?

Akide candy is often encountered during one of these ceremonies. It is a tradition that originated in the Ottoman palace.

The word "akide" comes from the Arabic root "akd/akit" (contract, commitment, agreement).

Akide candy is a mixture of sugar and water cooked at high temperatures. It is cooked at high temperatures until the water content drops to 2.0% or even 0.5%, after which it is often colored and flavored. During the seasoning stage, filled versions are sometimes produced, filled with cream, fruit preserves, sesame seeds, cinnamon, rose, etc.

This candy was presented to the Janissary soldiers after the meal following the distribution of their three-month salary (ulûfe). This candy can be considered a renewal of the contract between the soldier and the sultan. After the Janissaries received their salaries, the candy was presented; it was in the form of money.

This offering signaled the soldiers' satisfaction and loyalty. When a new sultan ascended to the throne, the weight of the sugar offered by the Janissaries was significant; around 400 grams of sugar was considered a sign of trust. If the sultan took the sugar in his hand and ate it, mutual trust was confirmed.

If the soldiers were dissatisfied with something, such as low pay, delays, or a lack of trust in the newly enthroned sultan, the cauldrons where the creeds were brewing were overturned. This is the origin of the expression "to raise a cauldron," which still exists in Turkey today, meaning to rebel.

In Tokat, Turkey, this function is evident in the form of Akit sherbet. Akit sherbet has become a symbolic beverage consumed during social reconciliation, commercial agreements, and important rituals. This sherbet, an important part of trade relations between village tradesmen and villagers, particularly in the Meydan district of Tokat, was used to ensure the security of trade.

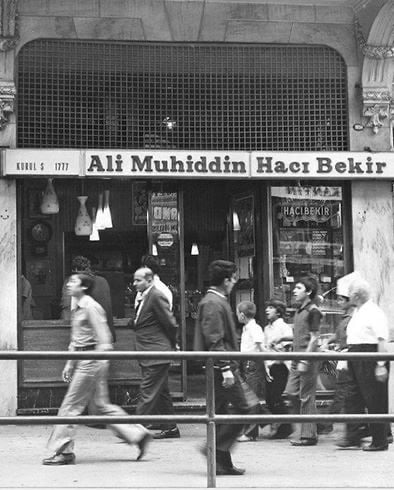

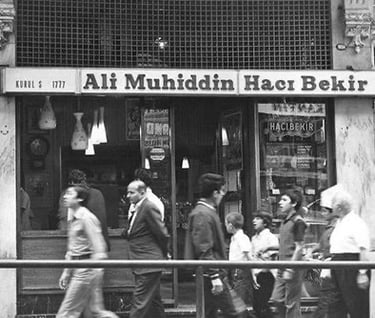

Akide candy originated in the palace in Turkey and has continued to exist ever since. This candy shop is associated with the name Hacı Bekir, which still exists today.

Hacı Bekir developed the production of akide candy by pounding the sugar, known as kelle şeker (head sugar), in mortars, melting it, and then cooking it with natural flavors and dyes such as rose, cinnamon, and other dyes. The palace recognized him and granted him the title of "Şekerbaşı" (Head of Sugar).

He was one of the first masters to use flavors like rose, cinnamon, orange, and lemon in akide candy. In this respect, he is considered a pioneer of modern sweet production and marketing in the Ottoman Empire. It is Turkey's oldest company. His shop is still open. Today, it is one of the 100 oldest brands in the world. The shop itself is a living museum. He made significant contributions to Turkish sweets with his inventions and techniques.

So How is Akide Made?

Sugar is boiled with water in copper cauldrons. The temperature is then 168 degrees Celsius. Then, it is poured onto a marble countertop and kneaded. If the countertop is at home, it can be oiled for convenience. Then, it is cut into pieces. Cutting with scissors is called Hacı Bekir Kesim.

The candy must be cut as quickly as possible. Otherwise, it will harden and become unshapable. Therefore, the craftsman must act as quickly as possible.

References:

Faroqhi, Suraiya. Osmanlı’da Kentler ve Kentliler. Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, 1993.

Oğuz Cam & Hakkı Çılgınoğlu, Hacı Bekir Efendi’nin Türk Tatlı Kültüründeki Yeri, TurAR Dergisi, 2024, s. 230‑232.

İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, “Hacı Bekir (Ali Muhiddin)” maddesi.

Sergy, F. (n.d.). A brief history of sugar. Retrieved from https://www.francoisesergy.com/sugar.htm

Karademir, Z. (2015). Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda şeker üretim ve tüketimi (1500–1700) [The sugar production and consumption in the Ottoman Empire (1500–1700)]. OTAM, 37(Bahar), 181–218. Özlü, Z. (2011). Osmanlı saray şekerleme ve şekerlemecileri ile ilgili notlar. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi, 58, 171-190

Demir, M. K., Elgün, A., & Avci, A. (2010). Klasik ve vakum altında spreylenerek pişirme yöntemlerinin akide şekerinin bazı kalite kriterleri ve raf ömrü üzerine etkisi. Gıda, 35(6), 431–438.

Özgen, M. (2024). Akide şekerinden doğan bir gelenek: Tokat’ta akit şerbeti ve etrafında oluşan ritüeller. Uluslararası Dil, Edebiyat ve Kültür Araştırmaları Dergisi (UDEKAD), 7(4), 948–959. https://doi.org/10.37999/udekad.1553608

Tasty Tools

Explore gastronomy.

Concact:

© 2025. All rights reserved.